How Does Disorder Organise Regulation?

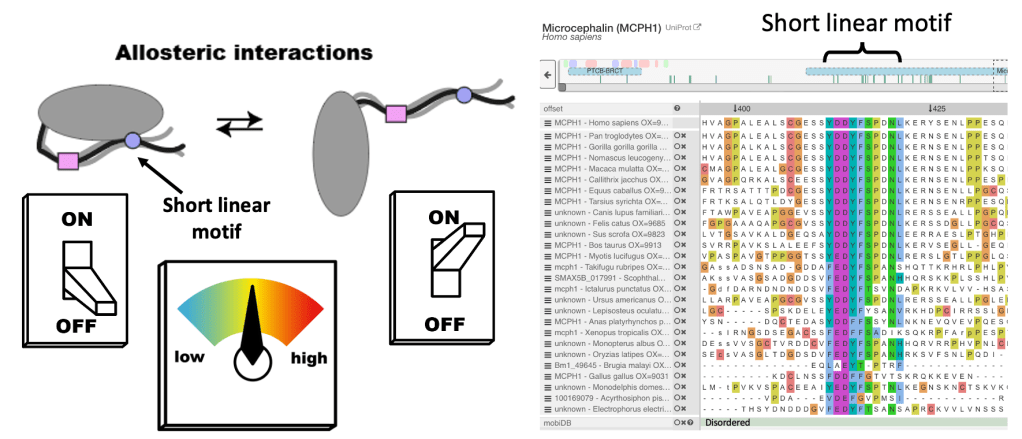

Highly conserved, disordered regions of proteins can make specific interactions that can drastically alter protein behaviour. These regions are called Short Linear Motifs, or SLiMs.

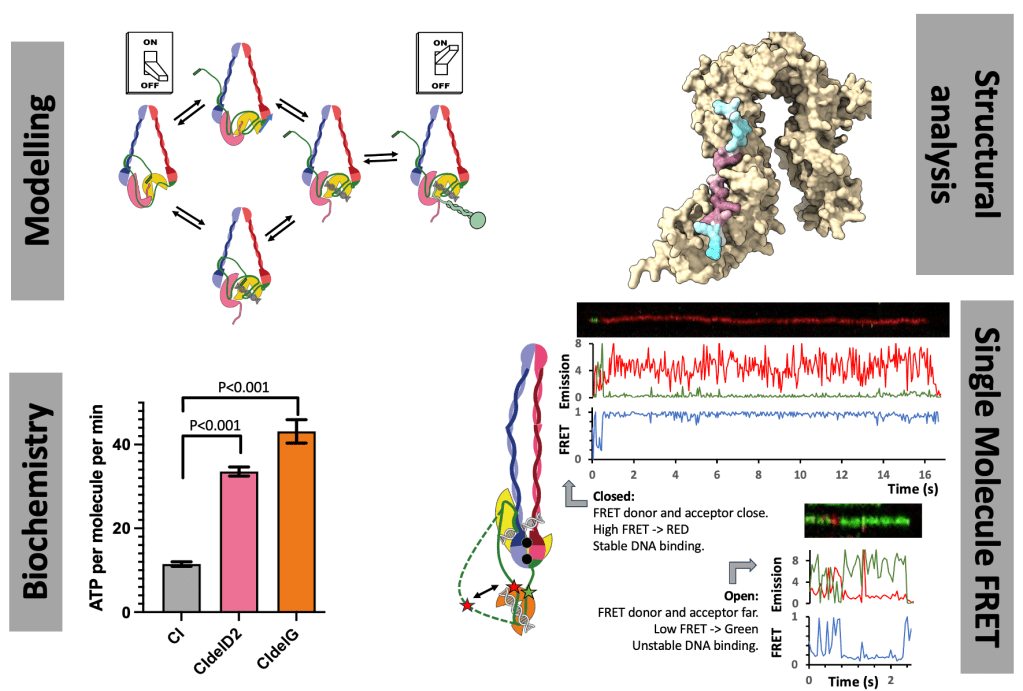

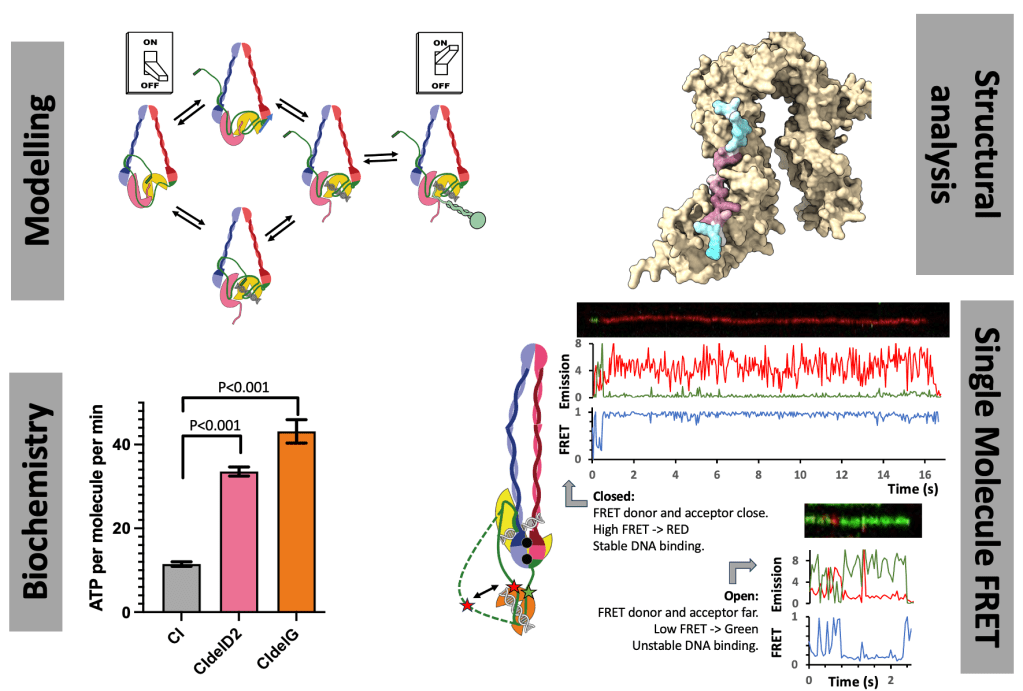

The human condensin complexes, responsible for forming chromosomes, are turned on and off by SLiM interactions, and while we know the key players, this is highly dynamic process. There are PhD projects in the Cutts Lab to understand how finely tuned regulation is achieved. Both projects use interdisciplinary techniques including protein biochemistry, structural analysis, single-molecule FRET and modelling.

One project, funded through the BBSRC DTP will collect single-molecule FRET data on Condensin complexes to understand regulation and binding.

The second project, funded through the DiMeN scheme will examine the role of DNA interactions and structural changes in resolving DNA entanglements.

Initial reagents and proof of principal data has been generated for both projects, providing a good foundation. There is scope to tailor projects towards specific interests.

Previous Projects

Visualising TOP2a in action!

When DNA is replicated, it can become tangled. TOP2a resolves these tangles, allowing cells to divide. The actions of TOP2a are essential for fast growing cancers, hence is the target of numerous chemotherapy agents. In this project, I used optical tweezers to braid DNA (in the figure in cyan) and visualise TOP2a (in the figure in yellow) resolution. Being able to visualise binding and resolution enabled new mechanistic insight into how TOP2a binds its substrate with ATP, how the conformation of the substrate effects this and how activity can be blocked by chemotherapy drugs or other protein complexes, such as cohesin, which holds two pieces of DNA together.

Looking at human condensin for the first time

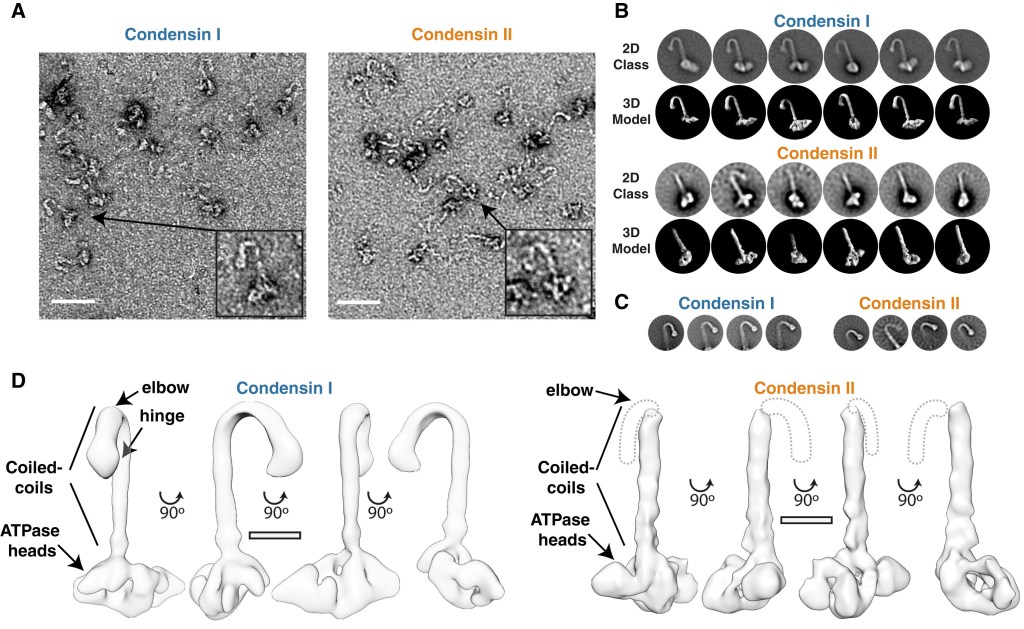

We have meters of DNA inside our cells, so how can all this length be separated into two daughter cells? DNA is compacted into chromosomes, thousands of times shorter, making them easier to divide. This compaction process is mediated by a protein complex called condensin. In humans, there are two isoforms condensin I and II, and much of my post-doctoral work focused on understanding the function and regulation of these complexes.

My first study on this was to characterise and compare of human condensin I and II. I could see they formed long complexes, which we can see in the EM data in the figure, that bound DNA, hydrolyses ATP and, in collaboration with the Green Lab, we showed condensin I and II could compact DNA, chromatin and loop DNA.

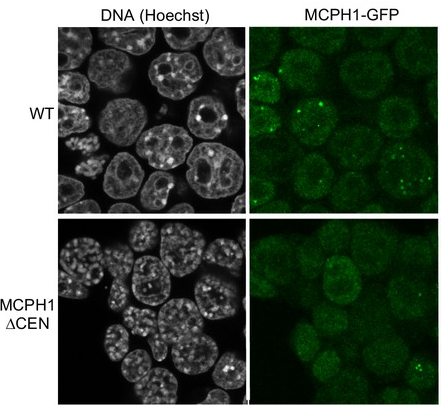

Turning Condensin II OFF

Condensin II is always in the nucleus, so why does it only compact DNA in mitosis? Mutations in the MCPH1 protein, which cause developmental disease, results in condensin II compacting DNA in interphase. In collaboration with the Nasmyth lab, I showed that MCPH1 bound condensin II via a central conserved “Short Linear Motif” or SLiM, and deletion of this “cen” region was sufficient to cause DNA condensation in interphase (shown in the figure). Short Linear Motifs play a huge role in regulating chromatin machines, hence exploring SLiM interactions is a key research theme of the Cutts lab.

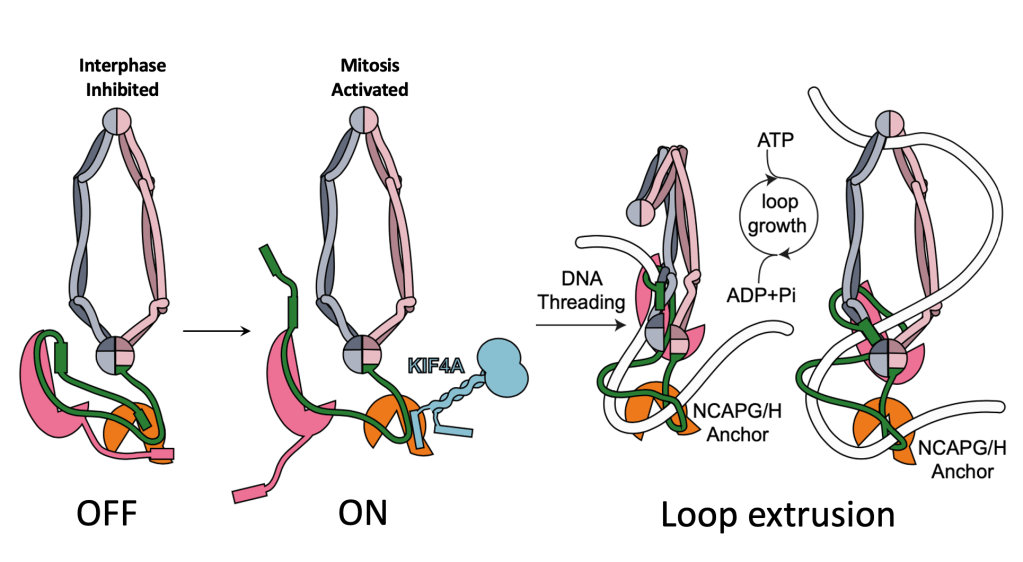

Turning Condensin I ON

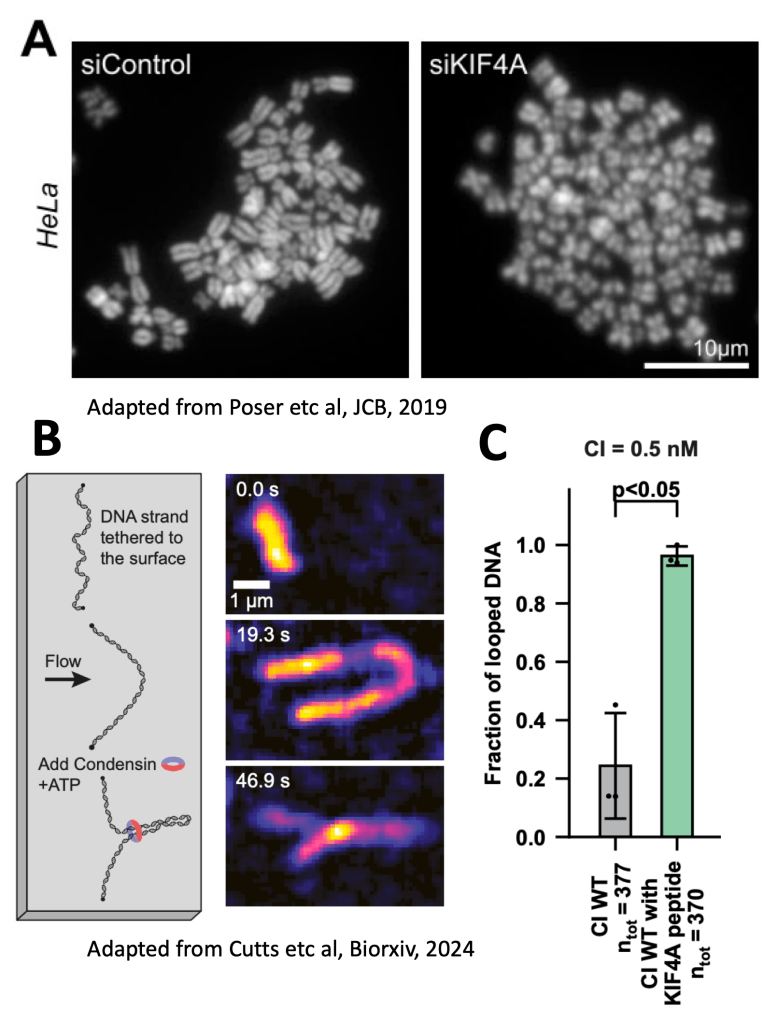

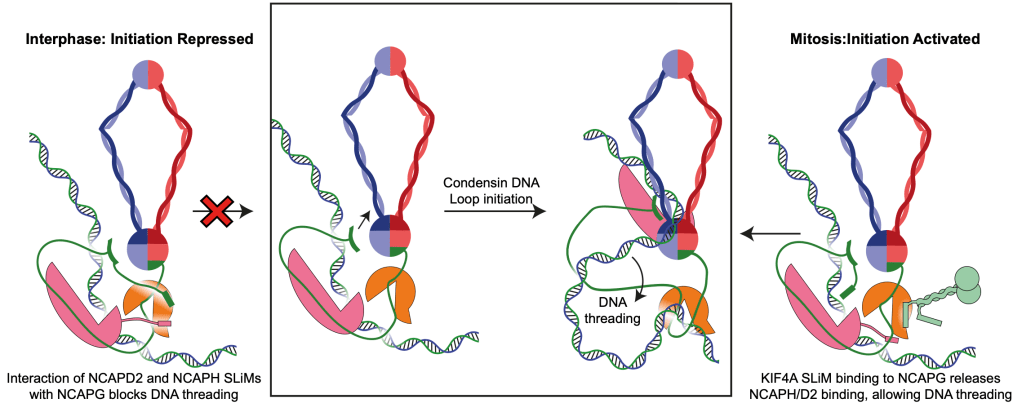

What about condensin I? Previous work found a kinesin, called KIF4A was needed for chromosomes to form correctly. You can see this in Figure A, from Poser et al, where KIF4A knock down makes chromosomes all fuzzy and fat. KIF4A had been shown to interact with condensin I and was required for its activity in cells, but we didn’t know the molecular mechanism. My work on condensin I suggests that in interphase it is autoinhibited by two “Short Linear Motifs” or SLiMs found in the disordered regions of NCAPH and NCAPD2, which bind NCAPG. KIF4A is able to activate condensin I by displacing the SLiMs of NCAPH and NCAPD2, and by just adding a short KIF4A peptide, we can see more condensin DNA loops in loop extrusion assays performed by our collaborators in the Kim lab (Figure B and C). This gives us a molecular mechanism, where KIF4A activates condensin I by allowing DNA loops to initiate, as shown in the below figure.

Malarial Infected Cells Get Stuck

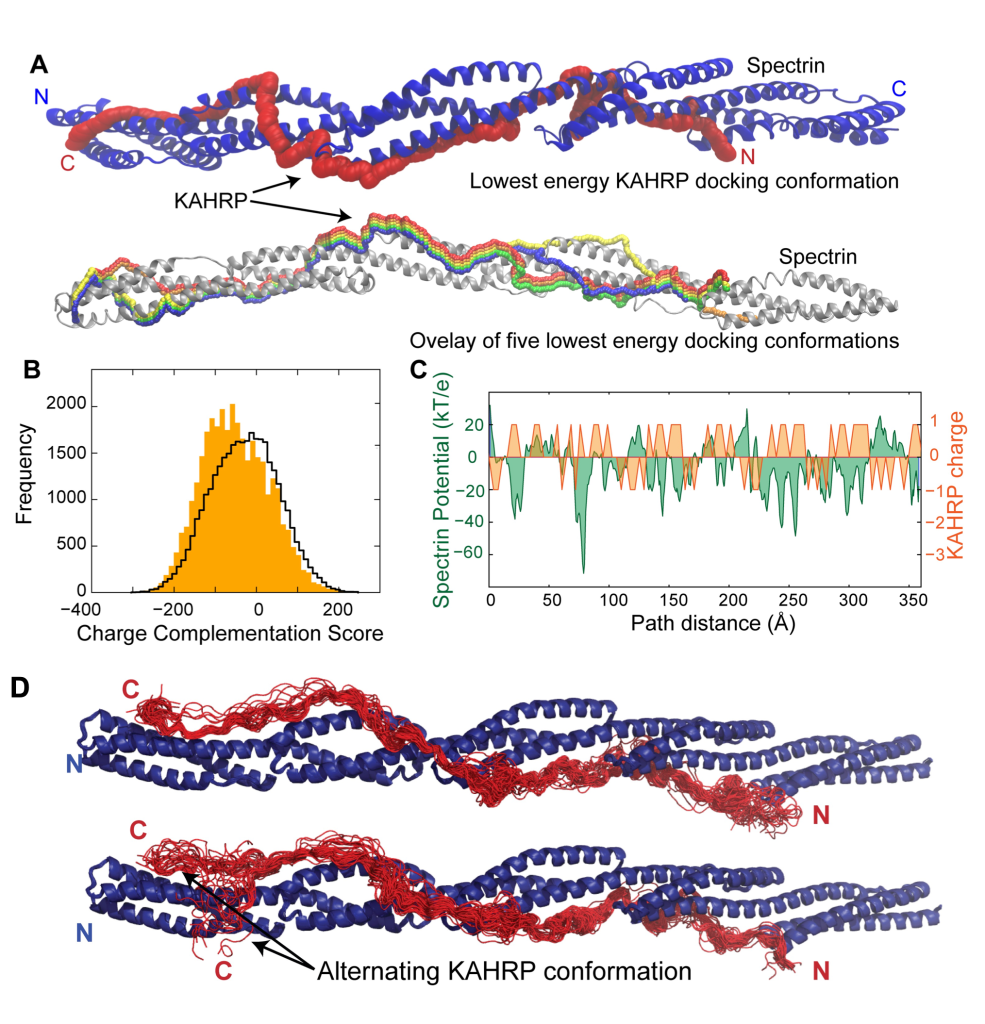

When the Plasmodium falciparum malarial parasite infects a red blood cell, it completely remodels it to its own advantage. This remodelling results in 3D protrusions forming on the surface of red blood cell, which cause “cytoadhesion” where the infected cells stick to the blood vessel wall, preventing immune recognition. I studied two parasite proteins, PfEMP1 and KAHRP, which contribute to cytoadhesion. Both have large disordered regions, that glue and anchor them to the host red blood cell cytoskeletal protein, spectrin. My work narrowed down these interactions to specific sites, which nucleate the formation of these protrusions. Working with disordered proteins has its technical challenges, and required a combination of computational structural biology, with NMR, crystallography and biophysics. I also came up with a novel approach to look at KAHRP binding by examining how a disordered protein interacts with a structured surface (figure A) optimising complementary surface charge (figure C). We then subjected the model to molecular dynamics simulation, and can see this is predominantly stable but can explore alternate conformations.

Making Static Proteins Dance

Most structural methods determine protein structure in distinct conformations, often in non-physiological conditions. I had multiple collaborations where I answered questions that arose from crystal structures using molecular dynamics. These include:

- Modelling a monomeric protein conformation from a crystallographic dimer, to better understand the interaction between the malarial proteins PfEMP1 and PHIST family members. https://faseb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1096/fj.14-256057

- Examining the dynamics of the flat beta sheet domain of the CPAP centriole protein. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3824074/ and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4613516/

- Modelling TolR, a component of the Tol-Pal complex important for outer membrane stability in gram negative bacteria, in a membrane, helping to support a model where TolR can undergo a large conformational change to bind peptidoglycan. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.671586

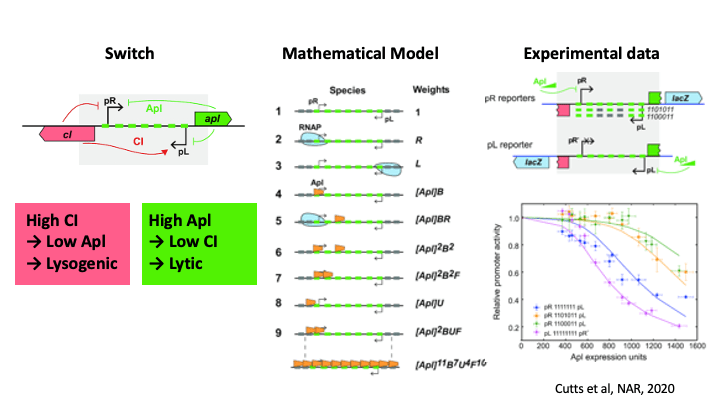

Pulling the Phage Ejector Switch

Bacteriophage can grow in two ways, lysogenically, where they integrated into the host bacterial genome, or lytically where they lyse the cell and grow like viruses. To decide between these growth modes, the bacteriophage 186 has a genetically encoded switch region which can be flipped by cellular conditions. The repressor protein, Apl, commits the phage to lytic growth, by binding to two sites; at the switch region, where it represses the promotor driving lysogenic growth, and also at the integration site, where it acts as an excisionase, promoting excision of the phage genome. I used mathematical modelling to understand how Apl binds using weak binding and cooperativity to form protein/DNA filaments to commit to lytic growth.